Masoud Pezeshkian, the sole reformist candidate in Iran’s recent presidential election, has emerged from relative obscurity to become the ninth president of the Islamic Republic. This surprising victory has sparked hope among Iran’s reformists after years of dominance by conservative and ultraconservative factions.

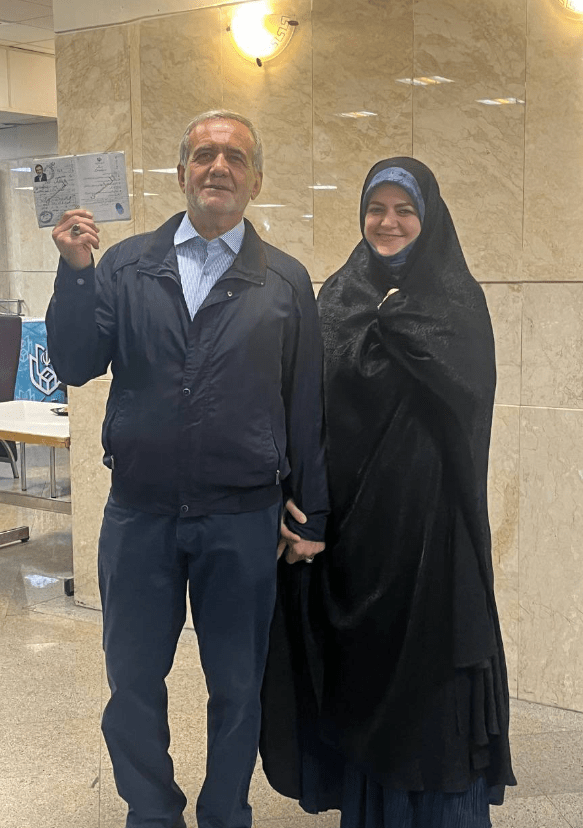

Pezeshkian, a 69-year-old heart surgeon, won around 53.6 per cent of the vote in a runoff election against the ultraconservative Saeed Jalili. His success in the first round of Iran’s snap elections on 28 June, where he led the polls against three conservative rivals, stunned both supporters and opponents alike.

Pezeshkian will take over from the late ultraconservative president Ebrahim Raisi, who tragically died in a helicopter crash in May. “The difficult path ahead will not be smooth except with your companionship, empathy, and trust. I extend my hand to you,” Pezeshkian declared in a post on the social media platform X, setting a tone of unity and collaboration for his presidency.

The rise of Pezeshkian has been bolstered by Iran’s main reformist coalition, with endorsements from former presidents Mohammad Khatami and the moderate Hassan Rouhani, adding significant weight to his campaign.

A Journey from Humble Beginnings

Born in 1954 to an Iranian father of Turkic origin and a Kurdish mother in the city of Mahabad in the northwestern province of West Azerbaijan, Pezeshkian’s journey to the presidency is a tale of resilience and dedication. He has represented Tabriz in Iran’s parliament since 2008, served as health minister in Khatami’s government, and supervised medical teams during the Iran-Iraq war from 1980 to 1988.

His personal life has been marked by tragedy. In 1993, Pezeshkian lost his wife and one of his children in a car accident. He never remarried, raising his remaining three children—a daughter and two sons—on his own. This personal resilience has shaped his political career, reflecting a commitment to public service and empathy.

Campaign Promises and Challenges

Pezeshkian assumes the presidency at a time of heightened regional tensions, including the Gaza conflict, disputes with the West over Iran’s nuclear program, and domestic discontent with the sanctions-hit economy. His campaign was marked by calls for “constructive relations” with Western countries to “get Iran out of its isolation.” He pledged to revive the 2015 nuclear deal with the United States and other powers, which had imposed curbs on Iran’s nuclear activity in return for sanctions relief until its collapse in 2018 when Washington withdrew.

Domestically, Pezeshkian has vowed to ease long-standing internet restrictions, a move likely to be welcomed by many Iranians. In 2022, he publicly criticised the Raisi government for its handling of the death in custody of 22-year-old Iranian Kurd Mahsa Amini, who had been arrested for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic’s strict dress code for women. Maintaining his stance during the campaign, Pezeshkian opposed the enforcement of mandatory hijab laws that have been in place since shortly after the 1979 Islamic revolution. “We oppose any violent and inhumane behaviour towards anyone, notably our sisters and daughters, and we will not allow these actions to happen,” he said.

Pezeshkian also pledged to include more women and ethnic minorities such as Kurds and Baluchis in his government. He has committed to reducing inflation, which he says has “crushed the nation’s back” in recent years and is currently hovering around 40 per cent. In a debate with Jalili, Pezeshkian estimated that Iran needs $200 billion in foreign investment, which he believes can only be achieved by mending international relations.

Navigating the Limits of Presidential Power

In Iran, the president is not the head of state; the ultimate authority rests with the supreme leader, a position held by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei for 35 years. As president, Pezeshkian will hold the second-highest ranking position and will influence both domestic and foreign policy. However, his power is limited. While he can set economic policy, he has little control over the police and virtually none over the army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which all report directly to the supreme leader.

Pezeshkian’s role will be to implement state policies outlined by Khamenei, a challenging task given the conservative dominance of state institutions. Parliament, dominated by conservatives and ultraconservatives, was elected in March. Parliament speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, who ran in the first round of the election, supported Jalili in the runoff, as did two other ultraconservatives who dropped out before the first round.

Facing an Uphill Battle

Political analyst Maziar Khosravi notes that Pezeshkian “did not promise an immediate resolution to problems” in Iran, acknowledging the significant challenges ahead. Ali Vaez of the International Crisis Group says Pezeshkian will face an uphill battle to secure “social and cultural rights at home and diplomatic engagement abroad.”

On the nuclear issue, political commentator Mossadegh Mossadeghpoor believes Pezeshkian may resolve it “if it is the system’s will.” However, diplomatic efforts to revive the 2015 deal with Washington and Europe have faltered over the years, and Khosravi cautions, “No one should expect Iran’s approach to foreign policy to fundamentally change.”