Following the October 7 attack by Hamas, Israeli forces have carried out sustained attacks on the Palestinian controlled territory, dividing the international community.

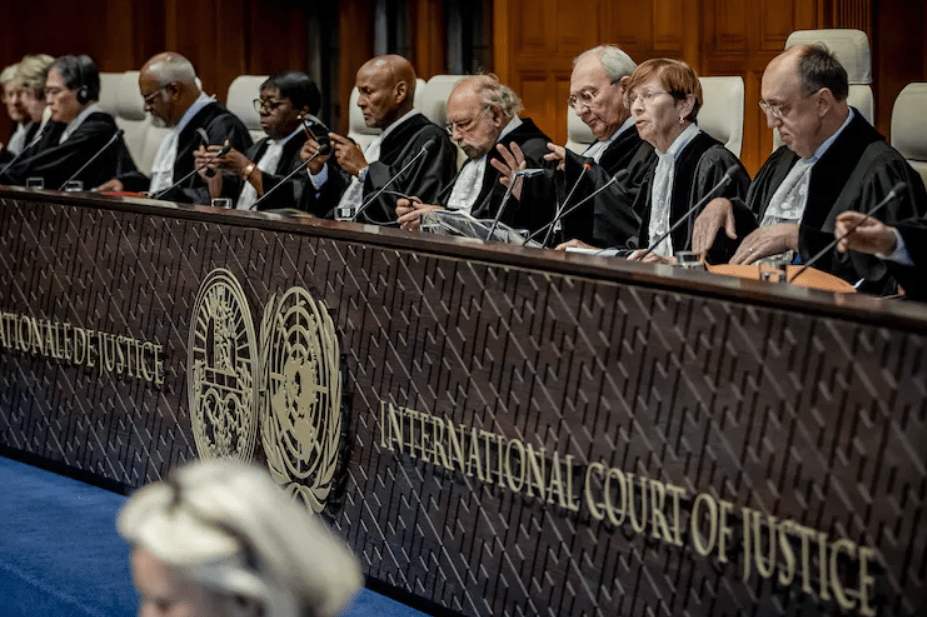

Last week, the South African government presented a case to the International Court of Justice. They argued the Israeli government’s attack on Gaza, and especially the actions of its forces within Gaza since early October, could amount to genocide.

Few cases that have gone before the court are as explosive and potentially significant as this one.

Here’s how the hearings unfolded and what happens now.

Defining genocide

The crime of genocide is covered in the 1948 United Nations Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

It is defined as acts committed with intent to destroy, either in part or in whole, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, including:

- killing members of the group

- causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group

- deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about a groups physical destruction, in whole or in part

- imposing measures to prevent births

- forcibly transferring children.

The Genocide Convention is designed to not only prosecute individuals and governments who committed genocide, but to prevent it from occurring.

Therefore, the Convention states that while genocidal acts are punishable, so too are attempts and incitement to commit genocide, regardless of whether they are successful or not.

The South African case

The South African government argued that Israeli forces had killed 23,210 Palestinians. Approximately 70% were believed to be women and children.

Crucially for the court, South Africa argued Israeli forces were often aware that the bombings would cause significant civilian casualties. It said many of the Palestinians were killed in Israeli declared safe zones, mosques, hospitals, schools and refugee camps.

Beyond the death toll, South Africa argued that there were 60,000 wounded and maimed Palestinians. The separation of families through arrest and displacement has caused large scale and likely enduring harm to civilians. South Africa highlighted the displacement of 85% of Palestinians, particularly the October 13 evacuation order which displaced over one million people in 24 hours.

The South African government also alleged the Israeli attacks and the actions of its forces were preventing the humanitarian needs of the Palestinian people being met. It particularly emphasised the Israeli decision to cut off water supply to Gaza. The distribution of food, medicine and fuel were also hampered. Israeli attacks on hospitals were also highlighted.

South Africa alleged the denial of adequate humanitarian assistance, especially medical supplies and care, amounts to the imposing of measures to prevent births.

Finally, South Africa focused on speeches by Israeli political leaders and soldiers advocating for the erasure of Gaza. This included Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s reference to the biblical destruction of enemies of ancient Israel and military commanders’ reference to Palestinians as “human animals” that need to be eliminated. These were used as evidence of incitement to genocide.

If the International Court of Justice doesn’t find that Israel is committing genocidal acts, South Africa has argued the Israeli forces have demonstrated an intent to commit genocide, and that there should be an interim order made to stop it.

The Israeli response

The Israeli government rejects all of the allegations by South Africa. Israel presented its arguments on January 12.

Israel’s overall argument is that the attacks on Gaza have been directed at Hamas soldiers. It says the civilian casualties have been an unfortunate consequence of carrying out military operations in an urban environment. Accordingly, the deaths, injuries and damage are not genocidal in nature, but instead, are incidental to military action.

Israel has presented evidence that it is delivering food, water, medical supplies and fuel to Gaza, demonstrating the opposite of genocidal intent. The Israeli Defence Force also runs a Civilian Harm Mitigation Unit.

These actions, according to Israel, are “concrete measures aimed specifically at recognising the rights of the Palestinian civilians in Gaza to exist”.

Finally, Israel has argued that the quotes South Africa have argued display incitement to commit genocide have been taken out of context. According to Israel, the court has no grounds to find that there are acts of genocide taking place, or that there is genocidal intent.

At this point, the court will not decide whether Israel has committed genocide or not. Determining that will likely take several years. Instead, the court will decide whether the allegations are at the least plausible, and if so, likely order that Israel and Palestine reach an interim ceasefire, and for Israeli forces to take all necessary steps to prevent genocide.

How significant is it?

If the court rules in favour of South Africa, a major world power – supported by the US and much of the Western world – will have been found to have committed what has, historically, been the most notorious of crimes.

That said, the prospect of any ruling by the International Court of Justice having a meaningful impact on the conflict in Gaza is remote.

The UN and its legal institutions are powered solely by a belief the international community is respectful of international institutions and international law. The problem is when a powerful country does not believe a ruling by a United Nations body applies to them, little can be done to enforce it.

The case of Nicaragua vs the United States in 1986 shows this in stark detail. The US initially indicated it would respect the decision of the court, but when the court found against the US, the US simply ignored the decision. For Israel and for its most powerful supporters, a finding against it by the court would likely be something they dispute and ultimately ignore.

Where does this leave Australia?

There is, however, a possibility the ruling could influence smaller powers.

Small to middle powers that rely on international rules to further their interests may be moved to support the cause for a ceasefire more vocally.

The Australian government would find itself in a particularly awkward position.

After all, the Australian government supported Ukraine’s case against Russia, also about genocide.

It has already made a public statement calling for restraint from Israel.

Australia would face a decision between unequivocal support for a country it sees as a partner, or support for a court it would otherwise see as a key arbiter in the international order.

This article was produced by The Conversation.