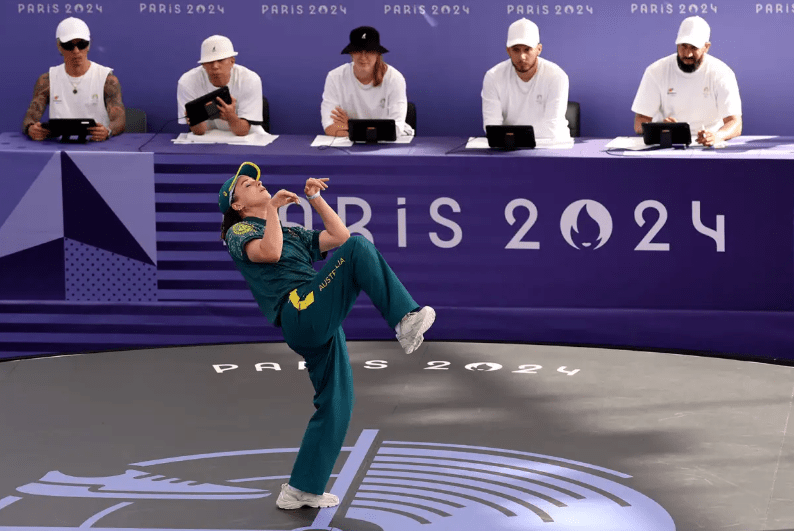

Rachael Gunn, also known as “b-girl Raygun,” has become a focal point of controversy following her performance at the 2024 Paris Olympics this week.

The 36-year-old professor from Sydney, Australia, quickly achieved internet fame—not necessarily for her Olympic prowess, but for a routine that sparked significant debate.

Competing against younger b-girls, Gunn was eliminated in the round-robin stage with an abysmal score of 18-0 in each of her three battles. Her unconventional moves, including a move dubbed “the kangaroo,” were intended to showcase originality but instead fell flat, leading to widespread ridicule.

Gunn’s viral moment seems to lend weight to rapper Azealia Banks’ critique that Australian culture remains stagnant due to its systemic neglect of First Nations talents and other people of colour.

Gunn’s performance, meant to stand out, became a showcase of white privilege, highlighting how Australia’s cultural landscape often overlooks its rich diversity.

Banks’ comments last year, where she described Australian culture as “trash” and criticised the country’s music industry for its post-colonial obsession, resonate with broader issues of cultural representation.

While Australia’s music industry has produced iconic acts like Kylie Minogue, INXS, and AC/DC, Banks argues that these successes are exceptions rather than the rule, suggesting that Australia’s music scene is largely stagnant. Is this a fair assessment?

This is Rachael Gunn, she has a PhD in cultural movement and convinced Australia to pay for her trip to the Paris Olympics.

She participated in break dancing and got 0 points.

— BowTiedMara (@BowTiedMara) August 10, 2024

Breaking (breakdancing), with roots in 1970s New York urban culture, emerged from the Black and Latino communities’ quest for creative expression and identity.

The dance style was a response to the marginalisation these communities faced and became a significant form of self-expression.

The fact that Gunn, a white Australian, was touted as the best breaker Australia had to offer highlights a critical issue: the prioritisation of white talent over those with more authentic connections to breaking’s origins.

Racial justice advocate and 350Australia Chair, Neha Madhok, criticised Gunn’s selection as indicative of Australia’s broader cultural biases.

“This is a reflection on the whiteness of Australian sport, and of Australian attitudes. We could have sent incredible people, the talent is absolutely there, but you have to go to where people are,” she tweeted.

“There are incredible dancers in places like Western Sydney (just one example) where black and brown people are honing their skills and their craft in arenas not recognised by establishment institutions.”

What the world needs to understand is that Raygun represents a very specific and uniquely Australian White Woman ™️ in academia. One who is so intent on ‘decolonising’ that she’s done a full loop back round to colonising again

— Néha

(@MadhokNeha) August 11, 2024

Australia’s history is undeniably steeped in colonialism. The arrival of the British in 1788 marked the beginning of a brutal and systematic dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The effects of this colonisation are still felt today, manifesting in social, economic, and cultural inequalities. Indigenous Australians continue to face discrimination, and their cultural contributions have often been marginalised or outright ignored.

Banks’ assertion that Australia stomped the “blackness” out of its culture isn’t entirely without merit. For much of its history, Australia’s cultural policies and practices favoured European traditions while suppressing or excluding Indigenous voices.

The White Australia policy, which was in effect from 1901 until the 1970s, further entrenched this monocultural mindset, limiting the influence of diverse cultures on the nation’s identity. While Australia has made significant strides in recognising and celebrating its Indigenous heritage in recent decades, the scars of colonialism remain.

This unresolved history could very well contribute to what Banks describes as the country’s “culturally stale” environment.

In a 2023 paper co-authored by Gunn, it is noted that “The more culturally inclusive breaking community in Australia, freed of the politics of language, was more about what you could ‘throw down’ in breaking – your skills and style.”

This reflects a broader acceptance within the Australian breaking scene, with diversity across the community including Australians of Filipino, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chinese, Indigenous, and Anglo heritage, as well as breakers from Asia and Europe. Despite this, the early 2000s proliferation of breaking crews across the country highlights a complex landscape where issues of representation and privilege persist.

Gunn’s routine and the backlash against it reveal a deeper issue: while Australia’s culture may strive for innovation, it often does so without adequately reflecting its diverse population.

This raises important questions about whether Australia’s cultural exports genuinely represent its people and whether they resonate on the global stage.

So, was Banks right in calling Australia’s culture “trash”? The answer is nuanced. Her comments, though provocative, spotlight real issues within Australia’s cultural sphere, particularly the enduring impact of colonialism and the marginalisation of Indigenous and other diverse voices.

Australia’s cultural identity is indeed a work in progress. To address these critiques, the country must confront its historical injustices and embrace its full spectrum of diversity. Only then can it develop a cultural identity that truly represents its people and resonates globally.