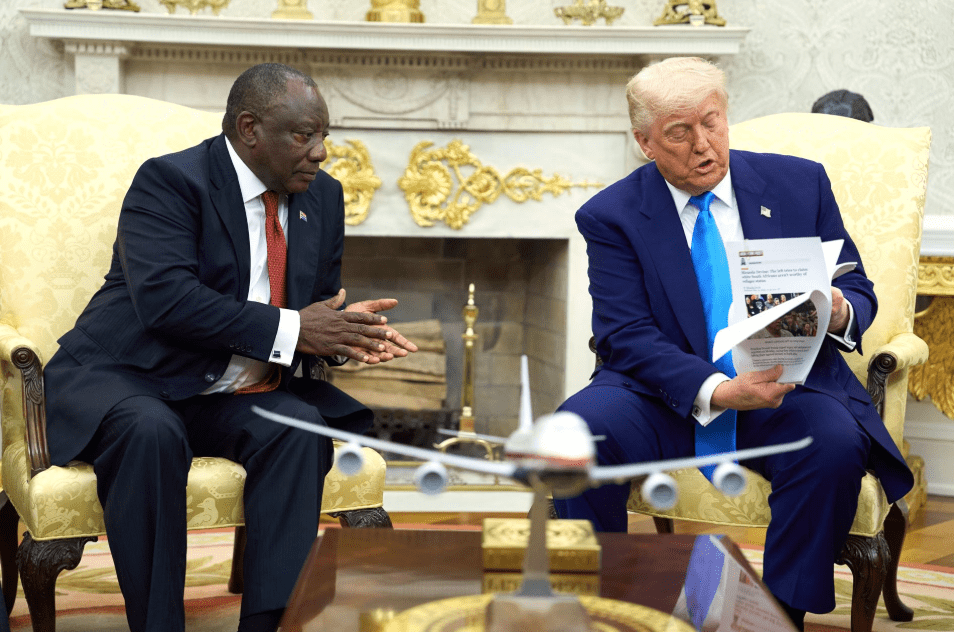

In 2025, U.S. President Donald Trump implemented a policy to fast-track asylum for white South African farmers, citing alleged “land seizures” and persecution — despite no credible evidence that these farmers met the internationally recognised definition of a refugee.

Critics pointed out the hypocrisy: while the U.S. sought to bar Central American families fleeing gang violence and political persecution, it was prepared to offer special protections to white farmers — a group often portrayed sympathetically by far-right media.

Many critics argued that the policy was not grounded in humanitarian concern, but in racialised politics—suggesting refugee systems are often manipulated to favour ideological allies over those most in need.

Under international law, refugee status requires a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership of a particular social group. General crime, economic hardship, or fears of land reform — as cited in the South African case — do not qualify.

This episode underscored how global North governments selectively apply refugee protections, often influenced more by race and geopolitics than actual risk. It also raises a crucial question: Who gets to be called a refugee? And who decides?

West Africa’s Overlooked Displacement Crisis — And the Rise of a Revolutionary Leader

While Syria and Afghanistan dominate global refugee headlines, West Africa is experiencing one of the fastest-growing and most overlooked displacement crises. In Burkina Faso, more than 2 million people have been forced to flee their homes due to escalating attacks by jihadist groups — a crisis that has unfolded largely outside Western media attention.

When Captain Ibrahim Traoré assumed leadership in 2022, he inherited a country on the brink. Years of mismanagement, corruption, and foreign military intervention had failed to curb violence, protect civilians, or stabilise the region. Traoré, then just 34, emerged as a symbol of resistance and renewal, vowing to reclaim national dignity and African sovereignty.

Under his leadership, Burkina Faso has cut military ties with France, reasserted control over key institutions, and promoted a Pan-African vision rooted in self-determination, anti-imperialism, and youth empowerment. Despite limited resources and immense challenges, Traoré has inspired a wave of optimism across the continent — particularly among Africa’s disenfranchised youth who see him as a modern-day Thomas Sankara.

Traoré has repeatedly voiced strong opposition to neocolonialism and foreign domination, framing his leadership as part of a broader movement to reclaim African sovereignty and dignity in the face of global injustice.

Still, the humanitarian toll remains severe. Aid groups continue to report restricted access to communities in need, and many displaced Burkinabè remain without stable housing, education, or medical care. But even critics acknowledge that these conditions did not begin under Traoré — they are the legacy of a long-failed system and foreign interference.

If Traoré succeeds, it will not only mark a turning point for Burkina Faso, but could redefine what African leadership looks like in a post-colonial era.

Global Injustice, Local Impact

The global refugee system is deeply imbalanced. Despite 150 countries being party to the Refugee Convention, just ten countries — mostly low-income nations like Pakistan, Uganda, and Turkey — host 60 percent of the world’s refugees. Meanwhile, wealthier nations tighten entry policies, fortify borders, and outsource responsibility.

In Europe, asylum seekers face growing hostility. From pushbacks at Greece’s border to delays in the UK’s processing system, protection seekers are often criminalised instead of supported. Even once admitted, they grapple with homelessness, unemployment, and racial discrimination.

Australia’s Hard Borders

Australia has a longstanding history of refugee resettlement, with over 958,000 humanitarian entrants welcomed since World War II. This figure is projected to surpass 1 million by late 2025, marking a significant milestone in the nation’s humanitarian efforts.

In 2023, Australia granted 29,892 individuals either resettlement or onshore protection—the highest number since 2016. This includes 14,669 asylum seekers recognised within Australia and 15,223 refugees resettled from overseas, placing Australia third globally in refugee resettlement numbers after the United States and Canada.

However, challenges persist. As of the end of 2023, there were 82,625 unresolved asylum applications in Australia, reflecting a persistent backlog. Meanwhile, offshore processing remains contentious. As of November 2024, 101 asylum seekers were detained on Nauru—the highest number since the Rudd-Gillard era.

The country’s immigration stance further hardened in December 2024 when the Migration Amendment (Removal and Other Measures) Bill 2024 received Royal Assent. Initially introduced in March 2024, the bill empowers the Immigration Minister to designate specific nations—such as Zimbabwe, Iran, Iraq, South Sudan, and Russia—as “removal concern countries.” Nationals from these countries can be barred from applying for any Australian visa.

The legislation also allows the government to compel individuals to cooperate with their removal, with non-compliance carrying penalties of up to five years in prison. The bill faced fierce backlash from human rights groups and community advocates. The Australian Greens called the law “divisive and cruel,” warning it could erode multicultural cohesion and lead to forced family separations.

The Zimbabwe Australia Cultural Association also raised concerns over the bill’s narrow definition of family, warning it does not reflect the broader kinship models common in African cultures. Critics argue the legislation contradicts Australia’s international obligations under the Refugee Convention and undermines its reputation as a global humanitarian actor.

While Australia boasts a proud multicultural identity, its refugee policies tell a more complex story. Since 2012, thousands of asylum seekers arriving by boat have been sent to offshore processing centres in Nauru and Papua New Guinea — often languishing there for years without resolution.

Human rights groups, including the Refugee Council of Australia and Human Rights Watch, have repeatedly condemned conditions in these facilities. Reports detail overcrowding, inadequate healthcare, prolonged detention, and mental health deterioration. In some cases, self-harm and suicide have occurred while waiting for basic protection claims to be assessed.

Offshore detention has been widely condemned by legal and human rights experts, who argue it is not only inhumane but breaches international law—particularly the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits returning individuals to countries where they face serious harm.

Refugees, Not Migrants

International law is clear. Under the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol — both ratified by Australia — a refugee is someone forced to flee their country due to a well-founded fear of persecution. Unlike voluntary migrants, refugees cannot safely return home. Asylum seekers, meanwhile, are those who have applied for refugee status and await a decision.

Yet, despite these legal distinctions, countless governments treat them as threats rather than survivors.

The Human Cost

Statistics rarely capture the psychological toll of displacement. Refugees often endure trauma long after reaching ‘safety’ — not just from past horrors, but from current neglect.

Zarlasht Halaimzai, who fled Afghanistan as a child, recalls the sense of abandonment after arriving in the UK: “We weren’t welcomed — we were warehoused. We lived in fear of being sent back.”

Now a writer and advocate, Halaimzai works to ensure that refugee voices are heard — not just spoken for.

Hope Through Policy Change

The crisis is not inevitable. What is lacking is political will.

Here’s what needs to change:

- Safe and legal pathways to prevent deaths at sea and curb smuggling networks.

- Timely asylum processing to minimise the mental health impact of uncertainty.

- Community-based alternatives to detention, which have proven both more humane and cost-effective.

- Investment in integration, including language education, mental health support, and employment pathways.

- Equal responsibility-sharing, with wealthy nations contributing fairly to global resettlement efforts.

More Than Numbers

Refugees are not statistics — they are teachers, artists, engineers, and parents. When offered safety and dignity, they often give back more than they take.

As global displacement reaches record highs, the choice before us is moral as much as political. Will we meet this moment with fear — or with humanity?