Australia recently held a historic referendum, the first in nearly 25 years, for a Voice to Parliament, a mechanism aimed at amplifying the voices of First Peoples in shaping the nation’s political landscape.

Voting “yes” would have meant officially acknowledging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the nation’s original inhabitants by establishing a Voice to Parliament advisory body in the constitution.

This generated intense debates and, in a resounding outcome, the entire nation, except for the ACT, ultimately voted “no” to the proposal, with over 60 percent of the Australian population opposing it.

The Voice to Parliament referendum aimed to establish a constitutionally enshrined advisory body, which would also provide Indigenous Australians with a platform to influence government policies that directly affect their communities.

The idea gained traction after the Uluru Statement from the Heart was issued in 2017, which called for a “First Nations Voice” in the constitution. However, despite widespread support from Indigenous leaders, the proposal faced several significant challenges.

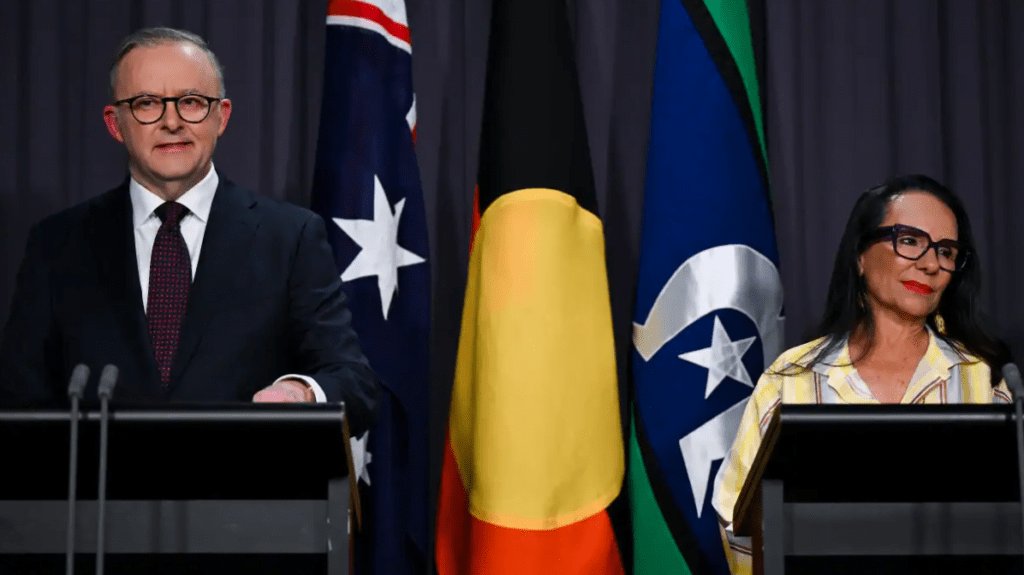

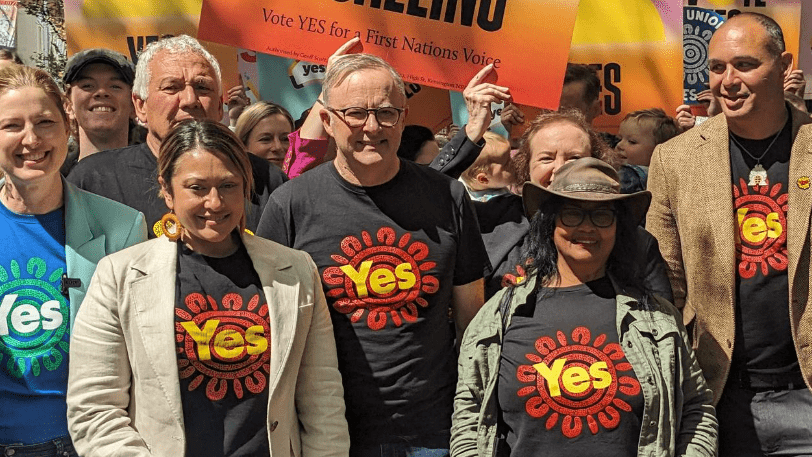

Prime minister Anthony Albanese accepted the referendum’s defeat and called for unity.

“This moment of disagreement does not define us, and it will not divide us, we are not Yes voters or No voters, we are all Australians. And it is as Australians together, that we must take our country beyond this debate, without forgetting why we had it in the first place,” Albanese said.

“Too often in the life of our nation, the disadvantage confronting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been relegated to the margins, this referendum and my government has put it right at the centre.”

One key factor contributing to the “no” vote was the lack of clarity and consensus surrounding the exact structure and functions of the Voice. Critics argued that the proposal was too vague and did not provide clear details on how it would operate.

This lack of specificity raised concerns about the potential for a “third chamber of parliament” or conflicts with the existing parliamentary system. Many Australians were hesitant to vote in favour of a proposal without a comprehensive understanding of its implications.

Another factor was the broader issue of public engagement and awareness. The Voice to Parliament proposal did not receive the same level of attention and public discourse as other voting events, such as the 2017 marriage equality plebiscite. Some Australians may not have been well-informed about the potential benefits of the Voice or the historical context of Indigenous rights struggles. This limited awareness likely influenced their decision to vote “no.”

Additionally, there was a strong undercurrent of skepticism about constitutional change. Australia has a history of referendums failing to pass, with only eight out of 44 proposals being successful. This track record of constitutional reform failure might have deterred some Australians from supporting the Voice to Parliament proposal, as they may have believed it was too ambitious or unlikely to succeed.

Furthermore, concerns about division and fragmentation may have played a role in the “no” vote. Critics argued that creating a constitutionally enshrined Voice for Indigenous Australians could lead to further division along racial lines. Some worried that such a mechanism might inadvertently reinforce the idea of separate treatment for different groups within the population, rather than promoting unity and equality.

The “no” vote also highlighted the political dimension of the referendum. In the lead-up to the vote, the proposal faced opposition from certain political quarters. Some politicians expressed reservations about the idea of an Indigenous advisory body with constitutional backing, fearing that it might interfere with the parliamentary process or create a precedent for other groups seeking similar representation.

Despite the “no” vote, the referendum sparked a robust national conversation on Indigenous rights and reconciliation. The debate surrounding the proposal brought to the forefront the need for genuine efforts to address the historical and ongoing challenges faced by Indigenous Australians, including issues related to land rights, health, education, and socio-economic disparities.

Ultimately, the “no” vote in the “Voice to Parliament” referendum can be attributed to various factors, including the lack of clarity about the proposal, limited public awareness, constitutional change skepticism, concerns about division, and political opposition. While the referendum did not result in the establishment of a constitutionally enshrined Voice, it has rekindled discussions about the importance of Indigenous representation and the need for ongoing efforts to address historical injustices and promote reconciliation in Australia.